THE DRUG WAR’S VISUAL REGIME

In 2016, Rodrigo Duterte was buoyed into the Philippine presidency through a campaign that maximized the use of online, digital platforms. For a seventy-one-year-old candidate with no social media account of his own, it was quite a feat. The online realm is highly visual and dynamic, structured as it is by an attention economy that demands the creation of copious amounts of eye-catching content. This success was propped by an organized team of advertising and public relations strategists (with seemingly predatory instincts for virality and a knack in skewing the algorithm for their client’s advantage), an emerging breed of political influencers and commentators, and an army of trolls.

With the presidency in the bag, the slew of online dominance from rabid followers continued. On one hand, supporters shared and bolstered posts, comments, hashtags, and images in praise of Duterte, and on the other, attacked actual or perceived political opponents. The armory of images, content, and abuse kept at a relentless pace. Then it was payback time. Influencers who had been supportive of Duterte during his run were hired in government posts and contracts. Here then was a form of governing that seemingly took the realm of digital images seriously. It invested and gleefully took part in the transaction of images, seeing the online world as a critical area where it can drum up support for various issues and personalities, while also reinforcing the state’s political power.

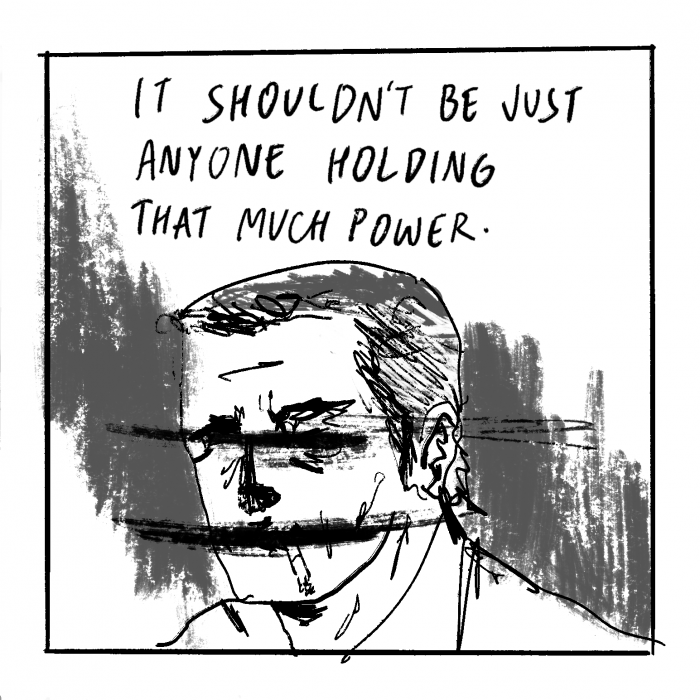

But perhaps this fascination with the visual can be partly attributed to the President himself. Duterte is a colorful character that demands public attention. Part comedic showman, part ruthless demagogue, his is a persona that lends itself towards hypervisibility, routinely stealing headlines and inciting extreme emotions with his antics, speeches, and gestures. As his predecessor monopolized the yellow color, Duterte’s characteristic fist bump, reproduced in numerous stickers and images and invoked in numerous photo ops, has been utilized as a sign of political allegiance. Other personalities, perhaps wishing to ride the coattails of his social and political largesse, had made use of this gesture. However, any absence from the public eye similarly incites rumor and controversy. His most recent public disappearance—made stranger by the release of grainy, night-time videos as proof of life—straddles a kind of gray area in terms of visibility, wherein political intrigue, information blackout, and presidential responsibilities (or lack thereof) seem to come to a head. This has led to comparisons with the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos who lied about his deteriorating health as he continued to cling to power.

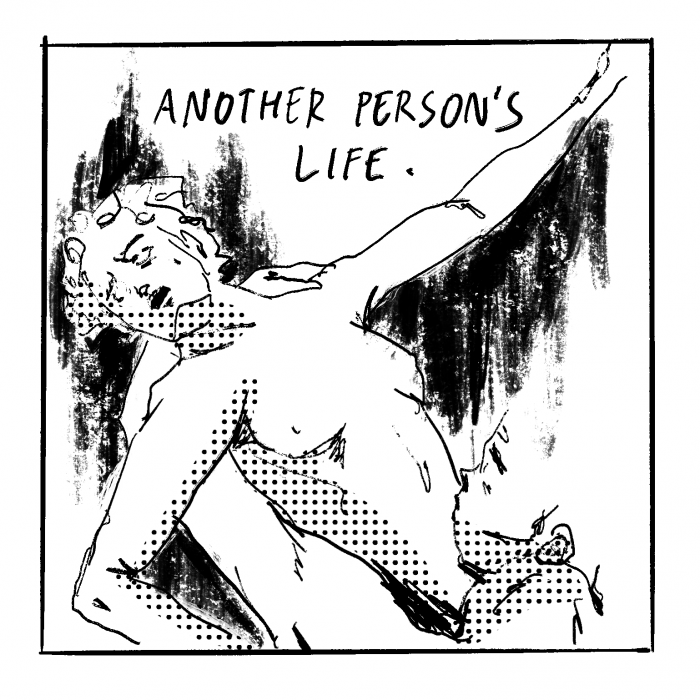

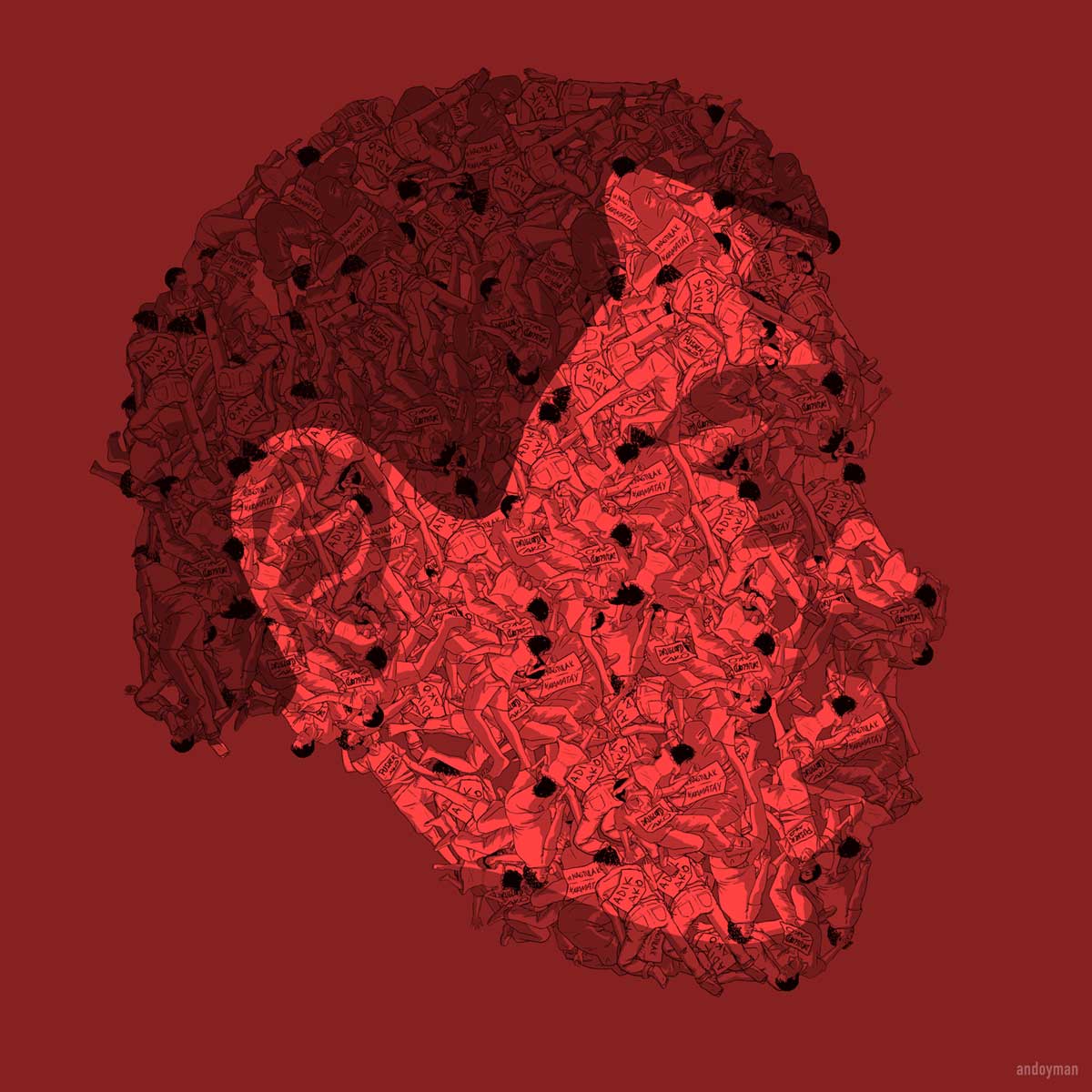

Duterte’s electoral centerpiece and long-standing obsession, the drug war, is similarly disposed to a regime of visuality. Support for it was aided by images and narratives of alleged crimes and victims of drug users, shared with alarm by social media influencers and supporters. It did not matter that some of these images provided false information, the waves of content and attacks threatened to silence any form of disapproval or criticism. In the drug war, photojournalists played a crucial part in documenting the ravaged bodies of supposed drug peddlers that counted as its victims. The victims were often poor and of the unwashed masses. However, images of the corpses—described by Vicente Rafael as the “fearsome signs” of the sovereign’s extralegal power and indomitable will— has not quite led to a straightforward incitement of public outrage, as hoped. At times, the photographs inspired mere passivity, fear, or acceptance of the project’s success.

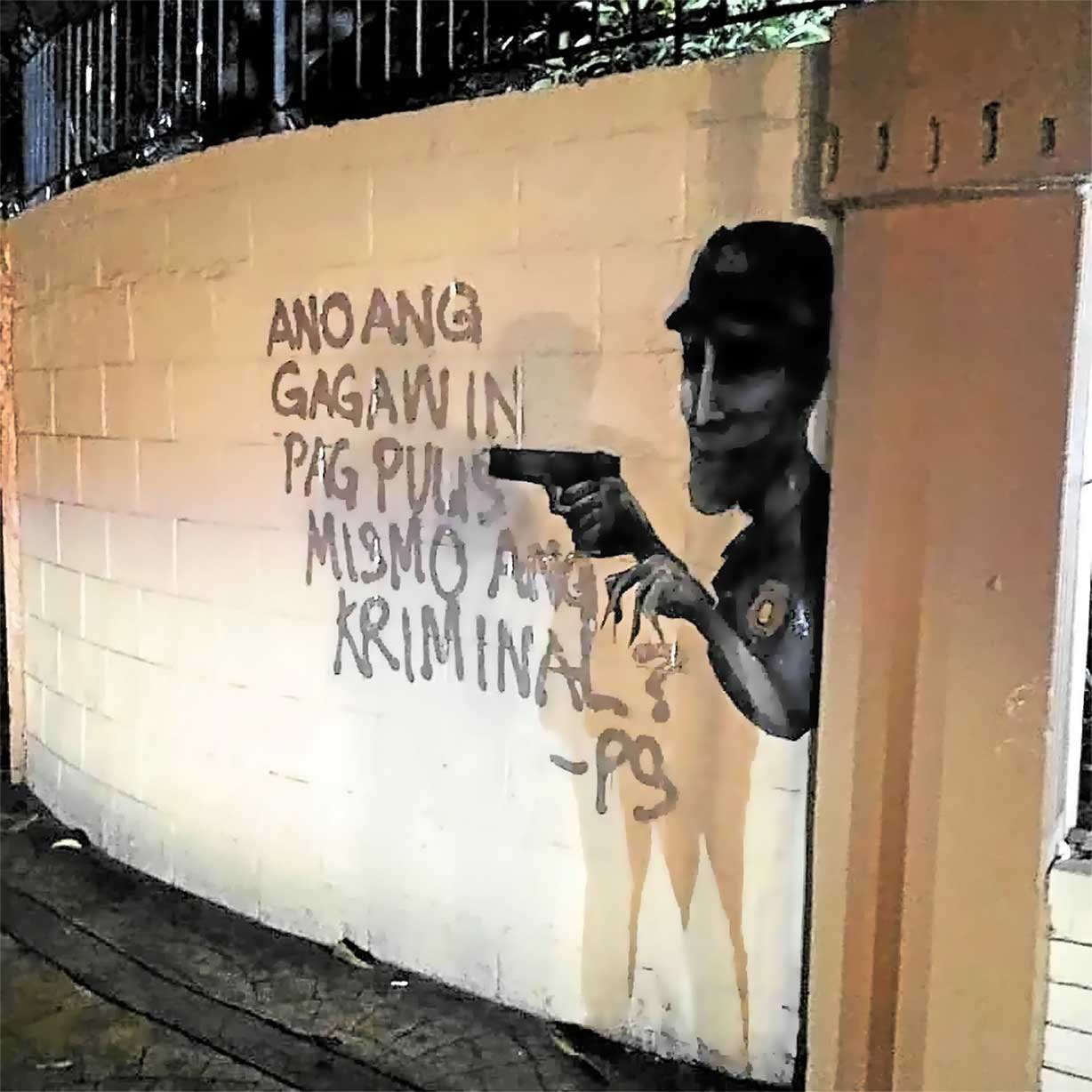

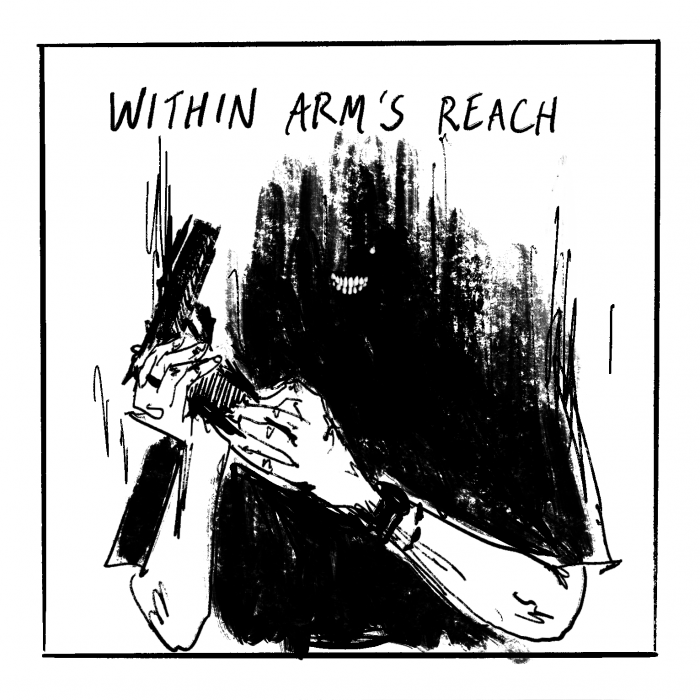

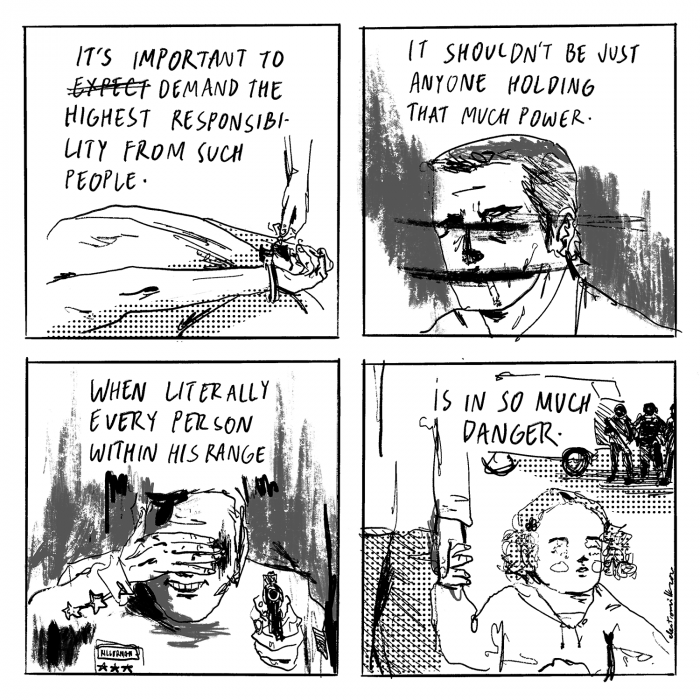

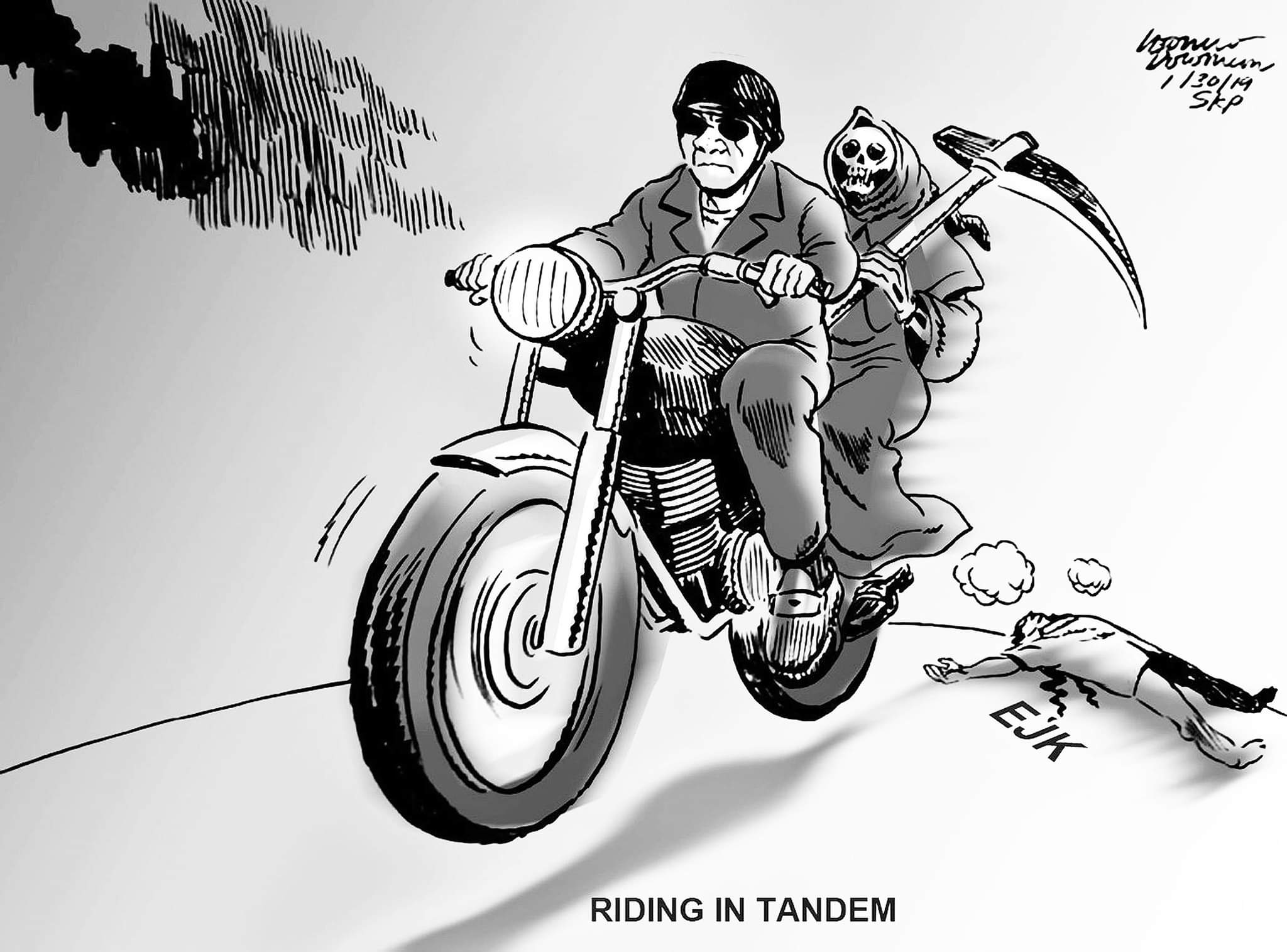

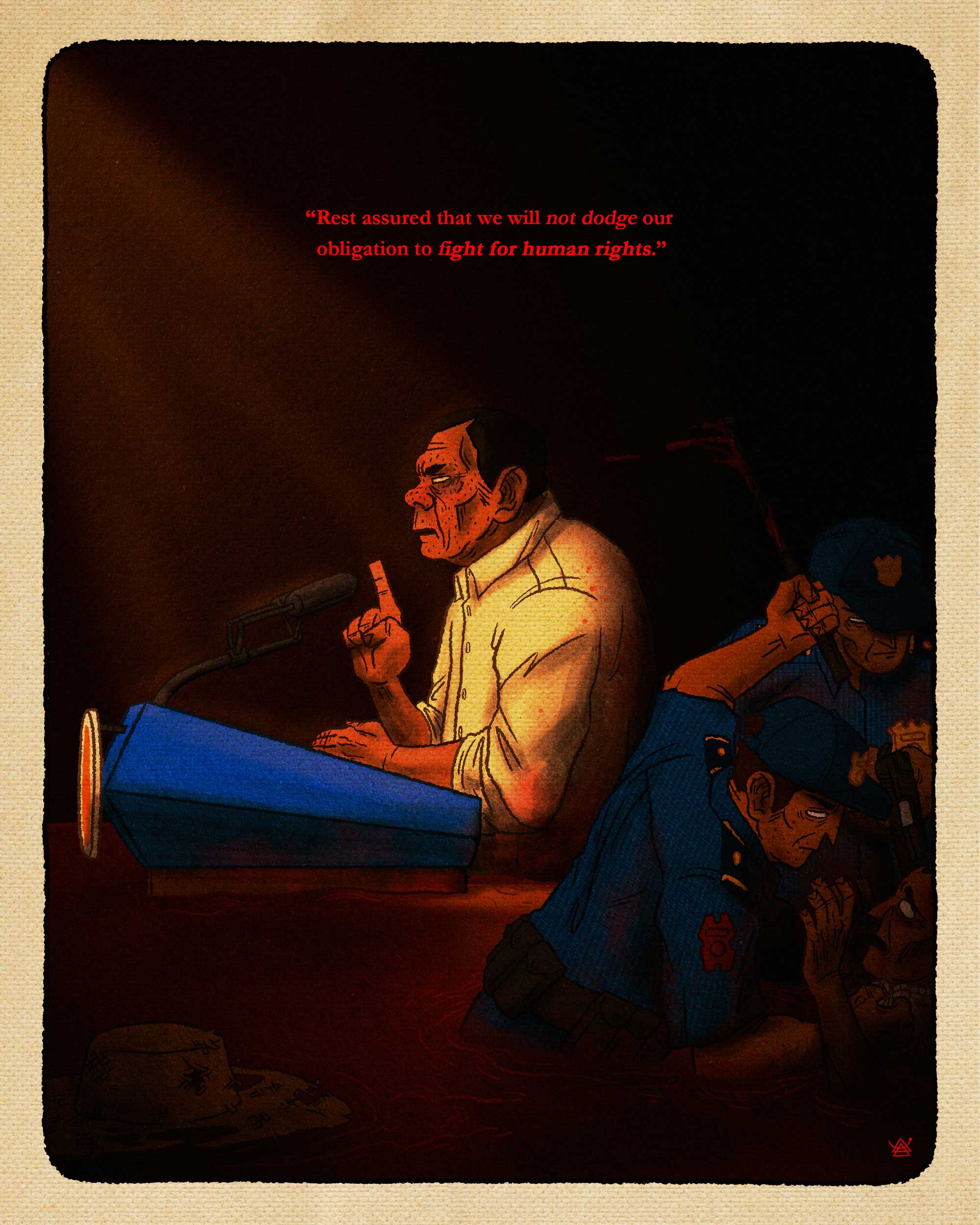

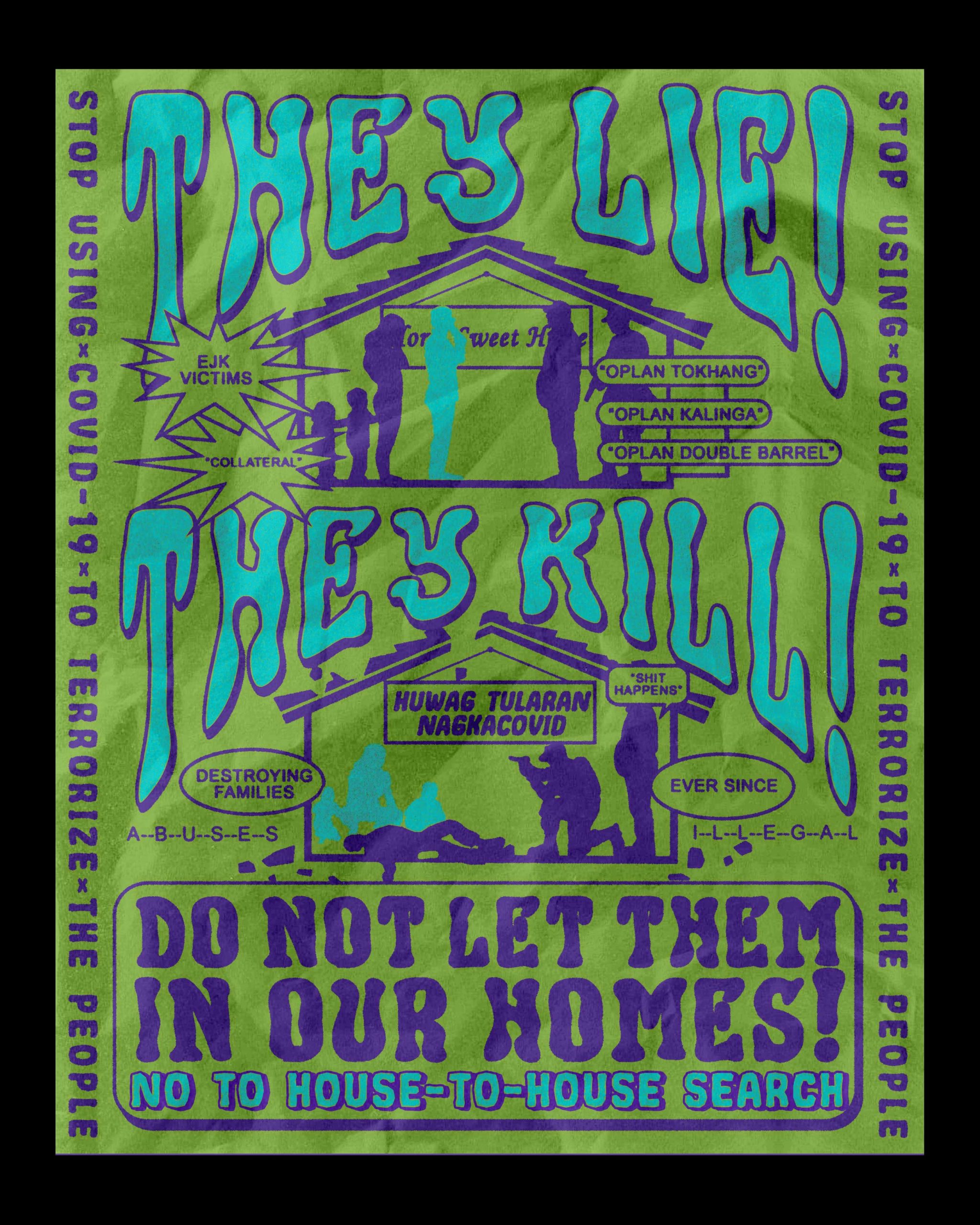

The works collected here take a slightly different track. By no means comprehensive, they present ruptures in populist (and online) discourse which have legitimized images, policies, and utterances that rendered segments of the population as subhuman. In a reversal of those traditionally determined as “social enemies,” here, the state agents, with Duterte at the helm, are the ones rendered criminally monstrous. As Duterte’s promise to rid the nation of drug lords, pushers, and users in the first six months of his administration started to fail, it mutated. Almost by design, the bloodlust of the drug war turned into the targeted killings of human rights defenders and the extrajudicial killings (EJK) of lawyers and anyone Duterte deemed criminal, in particular local government officials.

Highly political, these digital and editorial illustrations attempt to wrest meaning away from the sway of influencers, supporters, and trolls; and do so in the very same platforms in which these groups have dominated. The presentation of the works is an attempt to make legible and coherent a bloody war that has mostly unfolded in disparate corners, houses, and roads, and within the vicinities of urban poor communities, with an almost daily regularity. But the commensurate burden of transgression is shifted away from the victims. Instead, focus turns toward a far different set of personalities as visible targets, in the hopes that in doing so, condemnation and indignation can be further sharpened and channeled.

Download Full Exhibit Note

Exhibit note by Judith Camille E. Rosette, Instructor, Department of Art Studies, College of Arts and Letters, University of the Philippines Diliman

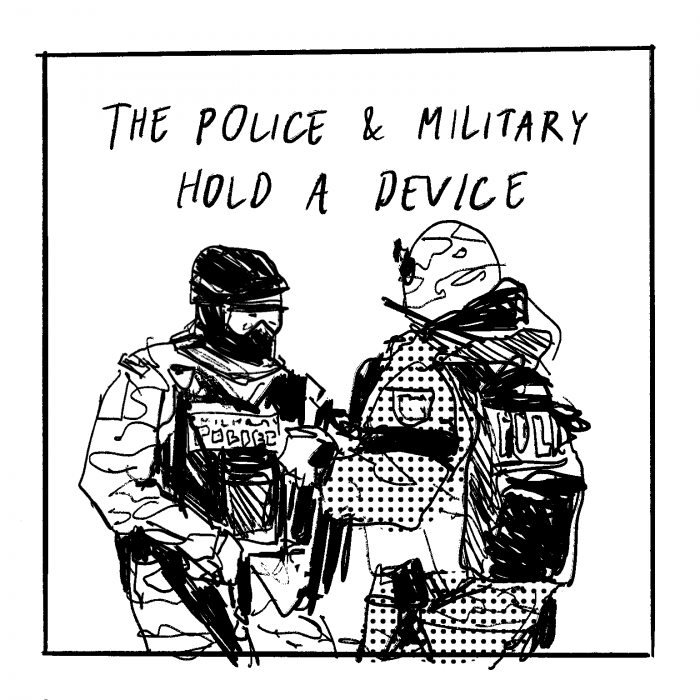

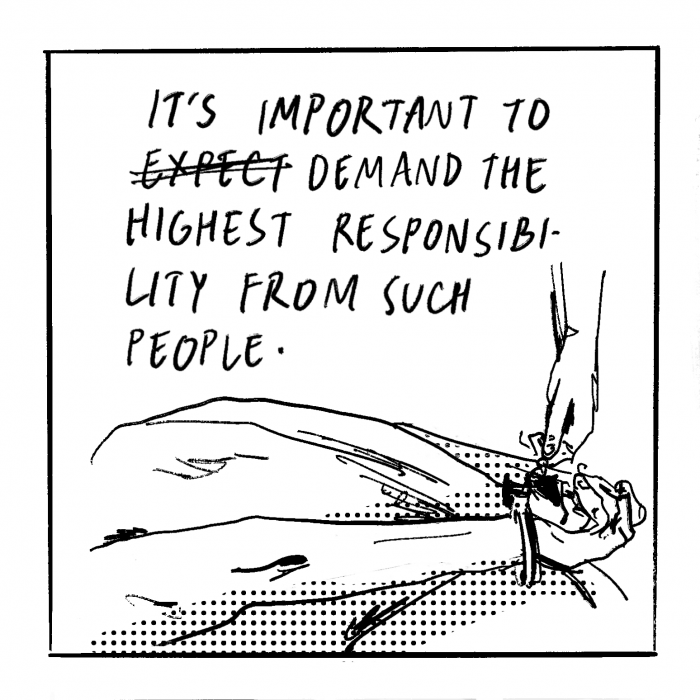

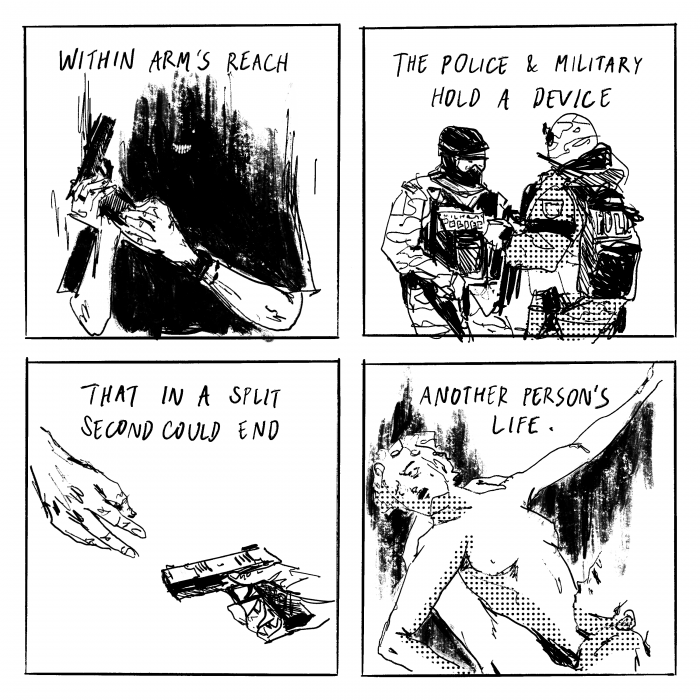

In the early years of the Duterte presidency, photographic images of the drug war often showed the outcome of drug operations. The sequence of events that led to the outcome were understandably left in the dark, allowing the state agents to write the now common script that the suspect attempted a fatal assault on them, forcing them to retaliate and kill the suspect. This entrenched the “nanlaban” narrative. An excuse for murder that also entails manufacturing and planting pieces of evidence, from shabu sachets to guns. These works explicitly point to the perpetrators and their motivations, while also foregrounding the catalyst that emboldened state agents.

“Pulis Games” by Emil Mercado

Captured videos of police killings have drawn the ire of a restless public that were already grappling with the economic effects of a pandemic. In as much as recent patterns of abuse and corruption are understood from the template of Oplan Tokhang, they may also open an avenue for the reassessment of the drug war. The recent push for the acquisition and use of body cams in police operations is illustrative of the ways in which their actions, and the drug war itself, are construed in the realm of the visual.

It seems that all roads lead to Malacanang. Throughout his presidency, Duterte has had no qualms in proclaiming his desire to rid the country of suspected drug pushers and users through mass killings. In these set of images, Duterte is rendered as perpetrator, enabler, and figurehead.

At a time when endless new emergencies distract from older issues, and in online spaces where it is far too easy to shuttle to the next viral topic, the importance of cohering events into a narrative acquires importance. In surfacing larger issues and establishing links, artists attempt to channel and make sense of collective anger, fear, but also, of hope. In the last image, a yearning for justice is evoked.

ALL ARTWORKS DISPLAYED HERE ARE USED WITH PERMISSION FROM THE ARTISTS AND/OR PUBLICATIONS CONCERNED. THE ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHS FOR THE STYLIZED BACKGROUND PICTURES WERE FROM RAFFY LERMA AND THE PHILIPPINE DAILY INQUIRER.

Featured Artists

ANDOYMAN

Graphic artist ang kasalukuyang trabaho. Pagkokomiks ang gustong gawin sa buhay. Madalas, procrastinator buong araw. Gamer mula gabi hanggang madaling-araw.

ELECTROMILK

Electromilk works as a high school teacher and freelance illustrator on the side. He is currently working on the horror-comics {Ang Manananggal}.

GILBERT DAROY

He was trained as a professional animator. After 20 years, he ventured into his childhood interest—political cartooning and caricatures. It is still what he is doing now.

PATO

Pato is a bootleg toy maker. He uses plastic resin, found materials and paint to make humorous figures of pop culture and everyday events. More of his work at www.gooeyduckph.com.

LEONILO DOLORICON

Professor Leonilo Doloricon was an artist, teacher, and activist, and was the dean of the UP Diliman College of Fine Arts. He was one of the leading figures of social realism in the Philippines, with many of his works highlighting social and political themes.

MAKÓ MICRO-PRESS

Makò Micro-Press is a mode of relationship or “ugnayan,” in the form of a self-publishing micro-press, which aims to create and sustain counter-hegemonic cultures through zines and other DIY (Do-It-Yourself) artworks.

MARX FIDEL

Si Marx ay isang ilustrador at komikerong mahilig gumawa ng art tungkol sa mga bagay-bagay na nangyayari sa paligid natin—lalo na sa mga usaping sosyo-politikal. Naniniwala rin siyang ang apoy ng paggawa at pag-asa ay laging nasa pusong sabik, galit at patuloy na umiibig. Umahon at magpatuloy!

PANDAY SINING

Panday Sining is a national performing group of artists aiming to create art as a medium for progressive expressions of national democracy.

TARANTADONG KALBO

Prior to 2020, this webcomic was more about the days in the life of a young couple and 1990s nostalgia. But during the pandemic, it became a biting mirror of the stumbling policies and statements of Rodrigo Duterte’s government in the eyes of the ordinary citizen. Through the brightly coloured and well-controlled art which represented key government personalities, the webcomics amplified in sharp relief the inequality of the rich and powerful against the poor and working class. It emphasized how erratic and confusing, and therefore unhelpful, many of the pandemic policies were. It sharply showed the inconsistencies and lies that came with official statements, in a way that was both angry and lighthearted at the same time.

TSAIIATTE

Si Maria Juvice Buñag o “Tsaiiatte” ay ipinanganak sa lungsod ng Maynila. Sa kabila ng pagiging isang estudyante sa kolehiyo, ipinupursigi rin ni Tsaiiatte ang maglikha ng mga obra sa pamamagitan ng ‘digital art’ na tumatalakay sa iba-ibang sabdyek o temang napapanahon. Bukod sa kanyang pampalipas oras sa paglilikha, siya din ay naging parte ng iba’t ibang organisasyon sa loob at labas ng unibersidad. Siya ay kasalukuyang graduating A.B Asian Studies student sa Unibersidad ng Santo Tomas, sa ilalim ng Faculty of Arts and Letters.

This exhibit is funded by the Office for Initiatives in Culture and the Arts, University of the Philippines Diliman.

Follow us on social media to get regular updates on drug-related killings in the Philippines.