(On December 4, 2019 Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana was quoted in media reports that he is not recommending to President Rodrigo Duterte the extension of martial law in Mindanao. The original declaration was made by President Duterte on May 23, 2017 in response to the attack on Marawi City by the Maute Group. Congress extended twice the martial law proclamation. The current declaration is due to end on December 31, 2019. This piece reminds of the consequences of martial law and militarization in Mindanao as suffered and endured by one of its indigenous communities.

This is an excerpt from a case study written by the author for the project, “Violence, Human Rights, and Democracy in the Philippines.” This excerpt was published by VERA Files on December 17, 2019. The project is a joint undertaking by the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman and the Department of Conflict and Development Studies, Ghent University. Augusto B. Gatmaytan is the director of the Ateneo Institute of Anthropology, Ateneo de Davao University.)

The unfamiliar buzz of drones overhead on October 15, 2017 prompted terrified Manobo residents to flee their homes in the hinterlands of Diatagon village in the southern province of Surigao del Sur’s Lianga town.

Location map. The inset map of the Philippines shows the location of Surigao del Sur province on the eastern coast of Mindanao island. The main map shows the relative locations of the town center of the municipality of Lianga (lower left of the map, along the coast of Lianga Bay), Brgy. Diatagon (midway between Lianga and San Agustin), and the community of Han-ayan (marked by a red pin).

Many residents thought the audible but invisible unmanned aerial vehicles that hovered above were there to deliver on President Rodrigo Duterte’s promise to bomb a tribal school in their sitio called Han-ayan.

On February 24, 2017, Duterte threatened to bomb indigenous schools such as those run by The Tribal Filipino Program for Surigao del Sur (TRIFPSS) and the Alternative Learning Center for Agricultural and Livelihood Development (ALCADEV), claiming they were operating illegally, without government permits, and were merely training grounds for communist New People’s Army rebels.

Months after his threat, Duterte declared all of Mindanao under Martial Law following Islamic State-linked militants’ siege of Marawi City on May 23 that same year. Since then, martial rule has been extended twice and will be in effect until the end of 2019.

While it was later learned that the drones used by the military were designed only for surveillance and had no offensive capabilities, they still cause anxiety whenever they fly over Manobo communities. The operations steadily eroded the indigenous group’s initial trust in Duterte.

The broken promise of change

The former Davao City mayor earlier enjoyed popular support among the Manobo, who have endured decades of government neglect and violence as early as the 1970s under the Ferdinand Marcos’ regime.

“Change is coming,” Duterte’s slogan during his presidential campaign, clearly resonated with members of the community. They have been seeking justice for horrible cases of violence suffered under the hands of the military and government militia.

On July 16, 2018, the Manobo of Han-ayan joined their neighbors in evacuating to the lowlands once more. This was in response to the presence of government soldiers establishing a series of military checkpoints in the area.

Witnesses complained the soldiers behaved so abusively (e.g., raucous and inconsiderate behavior, asking Manobo women where they can find the prostitutes in the village, pointing their assault rifles at villagers, interrogating people walking to or from their farms) that they could no longer endure the troops’ disruptive presence. Through all this, the military and the municipal social welfare office questioned the reason for the evacuation, repeatedly saying that there were no military operations then to warrant an evacuation.

Life under Duterte’s Martial Law

In the early morning of October 18, 2018, the sound of a drone was heard once more, circling over the village for more than two hours. The villagers had turned wary and anxious overnight; they ventured out less and kept their children close; and the entire community was markedly quieter.

Duterte’s martial law has caused profound uncertainty in the community’s life, where the possibility of violence at the hands of government forces and the painful necessity of again abandoning their homes and farms haunts every moment. This is heightened by the way the military seems to be isolating the communities within the Andap Valley Complex.

There is a widespread perception that the Manobo communities are being cut off from the government and from public services. When questioned, civil servants explained that they had been instructed by the military to refuse assistance to the Manobo. They said, “We cannot do anything [about this], because it is martial law now” (Wala mi mahimo, kay martial law karon), as if the declaration of martial law granted the military extraordinary control over the provision of public services.

At the same time, military officers and soldiers were quoted by tribe members as saying that under martial law, “Kami ang mahukmanon” (We [have the power to] decide [things]) and “Amo ang balaod’ (The law is ours), which seems to suggest that the military is claiming a greater voice in the political or administrative control of the area. It represents a twist on the current “whole of nation approach” to counterinsurgency, under which all government agencies are supposed to provide programs and services to local communities to persuade them against their suspected support of insurgent forces. Instead, what the Manobo experienced was a policy where all agencies denied them of services, and even respect.

There have been similar attempts by the military to sever the Manobo communities’ links to the wider economy. The most common form this effort takes is what the Manobo call “food blockades” where soldiers at checkpoints block, delay, or generally harass people transporting sacks of rice and other foodstuffs up into the hinterlands. This is apparent not only in how soldiers at checkpoints seek to control the flow of foodstuffs into the area, but also document and thus harass residents passing through.

There also seems to be an attempt to isolate the Manobo socially — to cut them off from their wider network of support beyond the communities. This takes the form of near-constant propaganda efforts that paint the tribal group Malahutayong Pakigbisog Alang sa Sumusunod (Persevering Struggle for the Coming Generations) or MAPASU and its officials as fronts of the outlawed Communist Party of the Philippines and its military arm, the NPA. Apparently, that is in order to erode outside support for the Manobo and their organization.

More pro-military propaganda placards.The lower photograph reads, “NPA [and] MAPASU, you [have] money-for-faces” , i.e., that the two are only concerned with amassing money, implied through the exploitation of the Manobo. (Both photographs by the author).

Placards or posters are also put up along the coastal highway that, among other things, purport to bewail how the innocent Manobo are being duped by the NPA, or which virtually equate the MAPASU with the NPA. The military has also weaponized judicial processes by filing false criminal charges for murder or kidnapping against MAPASU leaders. One effect of this measure has been to drive some of the accused leaders into hiding.

Beginning on December 31, 2018, and for days after that, the military conducted intermittent aerial bombing of the areas around the Manobo villages of Decoy and Panukmoan, prompting another evacuation.

Even as people were still reeling from that event, soldiers from the 401st Brigade of the Philippine Army patrolling the uplands of Brgy. Buhisan, San Agustin on January 24, 2019, inexplicably fired at four Manobo farmers. The farmers fled but two of them, Emel Tejero and Randel Gallego, both of Han-ayan village, were fatally shot. The slain men were described by the military as NPA rebels killed in an armed encounter, a claim disputed by the Manobo. Those were the first deaths due to militarization suffered under Duterte, underscoring the continuity of patterns of violence across decades and administrations.

One Manobo woman declared that “the symbol of martial law here is [the military’s] deployment of drones” (ang hulagway sa martial law diri kining pagpalupad nila og drone). Her statement captures what, for the Manobo, is the most salient characteristic of life under Duterte’s martial law: it is not just the continuing, virtually constant threat or reality of militarization, which, after all, is not peculiar to the Duterte administration. Rather, it is the community’s perception that they—Manobo residents of civilian communities—are actively being targeted by the state’s counterinsurgency forces and programs. Because each appearance of the UAV is, from bitter experience, linked to subsequent military ground operations, the drone is not merely an eye employed in surveillance, but is also a virtual gun sight used to aim the violence of militarization at Manobo villages.

Despite their clear civilian identity, they see themselves as treated the same way as the armed and insurgent NPA. The Manobo, of course, question why they are apparently being treated as targets of the state’s counterinsurgency violence alongside the NPA. In fact, a surprising number of community members said they did not oppose military operations as long as these were directed at the NPA and not at themselves, who are unarmed civilians.

Pro-military propaganda placards. The upper photograph reads, “[The Manobo] tribe is pitiful, [the] NPA is pitiless,” suggesting that the NPA is only exploiting the Manobo.

Most of them, however, asserted that the Manobo are being targeted by the military because there are corporations interested in the mineral wealth beneath the hills of the Andap Valley area. The military, in this view, is acting at the behest of these corporate interests by destroying or intimidating indigenous communities whose opposition to all mining operations in the area is articulated by MAPASU. The mining industry figures in the state’s notion of development, such that opposition to mining can and has been seen as opposition to the state itself.

But the community members seem to understate the importance of another reason for the military’s attitude toward the Manobo of the Andap Valley — the historical interactions between the indigenous group and the NPA. Those longstanding dealings perhaps allow the military today to simplistically equate one group with the other.

It is true that there are NPA units in the Andap Valley area. But while the Manobo first learned of their right to self-determination through Diocesan priest-turned-rebel Fr. Frank Navarro and the NPA, this does not necessarily make them members or supporters of the NPA. The Manobo, like other indigenous groups in Mindanao, have a tradition of political autonomy and self-governance which long predates the coming of the NPA. What the insurgents simply did was to give the Manobo the cultural and political resources to rearticulate their tradition of self-governance in the terms of the internationally recognized discourse on indigenous rights: “The right to self-determination.” Today, the Manobo are asserting their right to self-determination by, among other means, protecting their territory from the possible ravages of mining operations.

The Manobos of Han-ayan

The Manobo residents of Han-ayan live in a sitio or purok of around thirty households. After the Second World War, this area became part of the logging concession awarded by the government to Lianga Bay Logging Co. The Manobo profited little from these logging operations, however. Under such conditions, it is not surprising that the NPA was able to establish a presence there during the increasingly turbulent 1970s and 1980s as it waged its protracted guerrilla war against the Marcos dictatorship and the succeeding administrations.

The state responded to the NPA presence with militarization, and often violence resulted in the Manobos’ displacement from their homes and farms. Bishop Ireneo Amantillo of the Diocese of Tandag is widely recognized as having inspired the Manobo to organize themselves, eventually leading to their establishment of MAPASU in May 1996. In recognition of the needs and aspirations of the Manobo indigenous community, the diocese also organized TRIFPSS. This led to the establishment of a network of elementary-level schools among the Manobo villages in this area. Years later, the problem of ensuring the continuing education of the TRIFPSS’ elementary school graduates came up, so Manobo leaders worked with Catholic Church personnel toward the establishment of a local secondary school for aspiring students—ALCADEV in Han-ayan village.

Violence in Han-ayan: A partial history

The various versions of Han-ayan’s history naturally varied from person to person. In general, they all recounted a long, emotionally demanding series of human rights violations or abuses at the hands of the Philippine military and/or paramilitary forces, beginning in the 1970s and 1980s through to the present.

The first set of incidents all occurred in May 2005, when there were already ongoing clashes between units of the Philippine military and the NPA in the forests further up in the hills from Han-ayan. The residents of the villages of Mike and Han-ayan became particularly alarmed when they heard near-continuous gunfire drawing closer and closer to their villages. When the soldiers reached the village, they set up a perimeter around it, surrounding the assembled residents. The soldiers then accused three local men of being NPA supporters, and in full view of the villagers, proceeded to torture them. One man had a plastic bag pulled over his head and tied around his neck before finally being released. The two other men—who were brothers—were beaten by the soldiers, who clubbed them repeatedly with their rifles. The soldiers concluded the torture by binding their wrists and detaining them.

The second set of incidents was the September 2015 murder of three men by paramilitary members backed by soldiers of the Philippine Army.

In the early morning of September 1, 2015, the residents of Han-ayan were roused from sleep by armed soldiers from the 75th Infantry Battalion, who ordered them to assemble at the basketbolan (improvised basketball court) of Km. 16. Dionel Campos, then chair of MAPASU, and Belen Itallo, a senior teacher of ALCADEV, were made to sit on a bench, facing the residents assembled on the road. At around 5.00 a.m., two masked men stood beside Campos in front of the villagers, removed their masks, and introduced themselves as members of the Magahat-Bagani paramilitary group. They rebuked the villagers for their opposition to mining.

At some prearranged signal, the soldiers on the earthen banks beside the basketball court fired extended bursts from their assault rifles over the heads of the villagers. Meanwhile, one of the militiamen beside Campos forced him down onto the ground and shot him in the head with an assault rifle. Datu Juvello Sinzo, a community leader who was among the assembled villagers, fled down the road but was shot by another paramilitary man. Sinzo was still alive when the gunman approached his prone body and broke his limbs against the concrete sides of a water box he had fallen against.

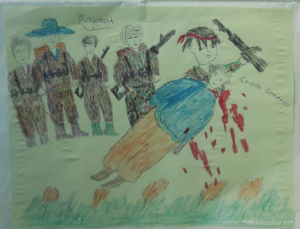

Later that morning, students found the bound body of ALCADEV Executive Director Emerito Samarca, dead from stab wounds and a slashed throat in his room at the school, where he had last been seen in the custody of other militiamen. Fearing further violence, Han-ayan and other Manobo communities evacuated. It took a year and two days before they felt it was safe to return to their homes.

Memory of a murder. This is a drawing by a youth, depicting the murder of Emerito Samarca, drawn as part of psychologists’ efforts to help the people of Han-ayan address the trauma of the event. (Source: Photo of artwork by Manila Today, featured and cited in Espina-Varona 2015).

Looking back today, some Manobo tribe members reflected that if there has been any change, it has been for the worse. While checkpoints and the filing of criminal charges have been part of the government’s counterinsurgency arsenal since the 1970s or 1980s, community members assert that their use today is more continuous or systematic and more closely coordinated with other means of social disarticulation. On the other hand, some of the measures are novel.

The formulation of an ethical and political response to violence perpetrated by the state against civilian indigenous communities entails a long, complex dialogue. Because of that, such a dialogue needs to be initiated soonest. The tales of the Manobo can help in this process, especially as their stories are not simply astonishing, or moving, or interesting, but most importantly, true.